How academic institutions can build diversity in health care research

New research in The Lancet Regional Health—Americas has found that academic institutions in Canada need to do more to recruit and retain racialized women in health care research.

The study from the University of British Columbia and the University of Toronto showed that primary care researchers who face racism, sexism and unconscious biases against parenthood, are most negatively impacted in their research productivity and career advancement.

Co-author Dr. Sabrina Wong, Professor at the Centre for Health Services and Policy Research and Associate Director of Research at UBC’s School of Nursing, discusses the challenges that women face in academia, and suggests strategies for institutions to create more equitable representation in primary care research.

Why is it important to look at race and gender in health care researchers?

Worldwide, we recognize that investing in health care research is essential for providing quality health care and building a strong health care system. We also know that diverse research teams who reflect different life experiences tend to produce more innovative research that represents the world’s populations.

Unfortunately, primary care research is underfunded and research productivity is low. Our study, which is the first of its kind, shows how systemic bias in the field continues to exist within Canadian institutions and society.

We interviewed 23 primary care researchers at Canadian institutions and found that the triple whammy of being a woman, racialized and a parent significantly and negatively impacts researchers’ productivity. Impacts include fewer career advancement opportunities, lower salaries and having less of a voice in the workplace. These findings add to previous work completed in the US but with additional insight from primary care researchers as well as how processes impact racialized women, many of whom are mothers.

These findings are troubling because we need women and racialized researchers to bring their valuable perspectives and insights to primary care research. Addressing these challenges on a systemic and institutional level is not just about fairness, but is necessary to advance health care and benefit society.

How can granting agencies and institutions support women and racialized faculty in health care research?

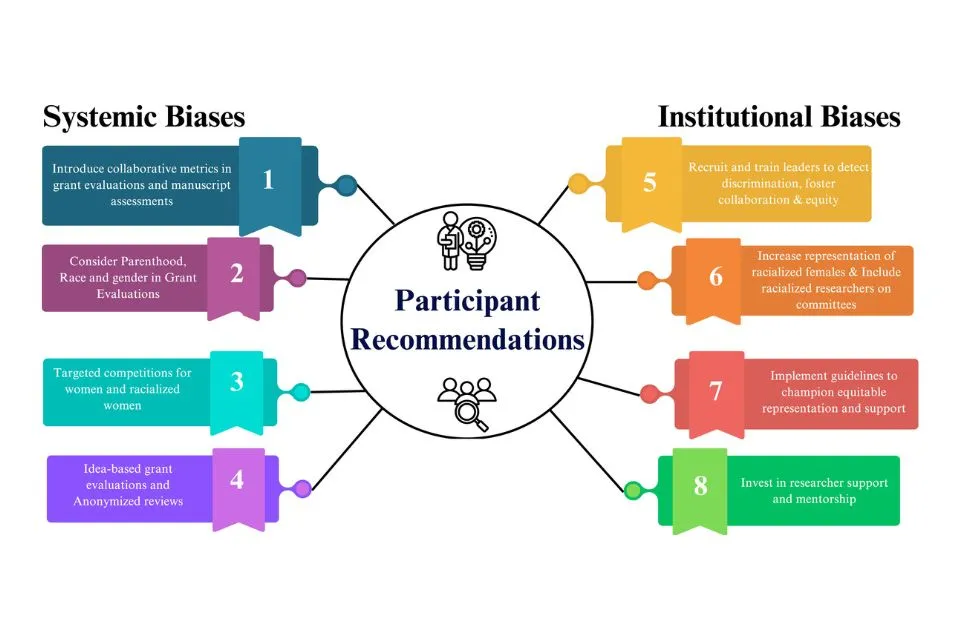

Research participants indicated a number of ways to combat systemic and institutional biases.

At the systems level, participants recommended that granting agencies consider the impact of race, gender and parenthood on research productivity, and to include competitions targeting women researchers specifically.

Granting agencies could consider “collaborative metrics” which positively reward grant submissions with diverse research teams and the degree to which institutions support diverse faculty.

Participants called for academic institutions to focus on recruiting deans and department chairs who will champion equity, increase racialized and female representation in leadership and faculty roles, and requiring diversity and implicit bias training for all involved in hiring and promotions.

To retain diverse talent in primary care, institutions can provide mentorship programs that pair early-career researchers with experienced mentors of similar backgrounds, mentorship teams or committees. Mentorship grants can support senior faculty for their mentoring contributions.

Institutions can also provide funds specifically for early career researchers, with a focus on breaking down barriers. One example of this is the Canadian Institutes of Health Research's Research Excellence, Diversity, and Independence Early Career Transition Award, which targets early career researchers impacted by race and gender inequality.

In addition, organizations can make a point to highlight researchers’ accomplishments and provide opportunities to build recognition through awards, speaking engagements and media exposure.

What has your own experience as a racialized woman in primary care research been like?

I became interested in primary care when I was a postdoctoral fellow at the Centre of Aging in Diverse Communities at the University of California, San Francisco. The racialized researchers I worked with were much-needed role models for how to overcome discrimination and parenting pressures to become an expert in their field.

Many of our study’s findings correlate with my own experience as a racialized woman in primary care research. The long hours, the weekends worked away for years, the effort to achieve as much as my colleagues who aren’t racialized, women or parents. The sacrifices and chagrin from family whose expectations of my role outside of work that conflicted with the needs of my career.

We need women and racialized researchers to bring their valuable perspectives and insights to primary care research.

As time passed, I recognized my ability to succeed in academia would not simply be due to the lessons engrained in me to “keep my head down and just work hard.”

I saw that despite my accomplishments, and the accomplishments of colleagues like me, that researchers who are not racialized (and particularly not women) are most likely to be offered important leadership positions. Ostensibly, this is sometimes due to “not having the right leadership experience,” but we have to ask ourselves: Are we giving racialized and women early career researchers the opportunities to develop the right leadership experience?

Opportunities to recognize and uplift our colleagues’ expertise are key to nurturing and retaining diverse talent. When I was a junior untenured professor, I was invited to join an initiative to lead and train the next generation of primary care researchers—and was specifically asked for my expertise in the area. This type of early career recognition helped to set me up for further leadership success in my own career.

It is therefore very important for me to provide those types of mentoring and leadership opportunities for the next generation of primary care researchers, and to do what I can to create a supportive environment for everyone.

We have to ask ourselves: Are we giving racialized and women early career researchers the opportunities to develop the right leadership experience?

For example, I am working to mentor and sponsor tenure-track junior faculty members through co-leadership of the BC Primary Health Care Research Network, supporting their grant leadership and important connections to policy makers, clinicians and others in this area of research.

At the UBC School of Nursing, I co-chair our anti-racism committee. We explore factors that may support or hinder the success of faculty and staff at an institutional level.

I am also part of a new project led by my study co-author, Dr. Monica Aggarwal, that will look at breaking barriers: Unveiling gender, racial and other intersectional dynamics in post-secondary institutions. The overarching goal of this work will be to meticulously identify and understand the multiple barriers encountered by women, particularly racialized women, at crucial junctures of their post-secondary academic career—upon entry, as faculty and when advancing to leadership positions—within the primary care and public health disciplines.