In his short-lived blog Pancreatic Times, Kevin Watson documented his struggles with cancer — his dance, he called it. On March 15, 2012 he shared his distaste for chalky tinctures, syrups, sticky energy gels. “I’ve been pretty clear that I don’t want people feeling sorry for me,” he wrote, “but given these remedies, I am asking you now.”

The blog, however, soon became difficult to write. On May 5, the 43-year-old apologized for his “lack of energy and creativity.” Five days later the father of two died at home while holding his wife Christi’s hand. His last blog entry reads, “Au revoir but not goodbye.”

Shortly after his passing, Pedal magazine ran an obituary and image of Kevin racing at a Toronto cycling competition. After all, Kevin’s life had many directions: besides being a father and competitive cyclist, he worked as a creative director at Shaw Media, determining the “look and feel” of History Canada and other specialty channels. “Kevin was self-admittedly a happy, fulfilled guy in every way,” says his father, Colin Watson.

While Kevin grew up in Toronto, the city of Vancouver loomed large in his early life. In the early 1990s, he attended UBC with his brother, riding his cyclocross bike through the thick-necked cedar trees around campus. No doubt Kevin often passed Acadia Creek — the unassuming stream that, decades later, and after his death, his family would restore in his name.

Of the over 100 streams in Vancouver that once bore salmon, only three are left: Musqueam, Spanish and Stanley Park’s Beaver Creek. Four streams, actually, if you count the one alternately called Salish by the Musqueam First Nation, Acadia or Hillary Creek by Google — and Unnamed Creek by Metro Vancouver. And while a city report designated Salish or Unnamed Creek as “one of the last, seemingly healthy streams in the area,” that bill of health was revoked in 1947 with the introduction of a culvert.

Few biologists assumed coho salmon could ever wriggle through the barrier, let alone spawn upstream. In 2011, however, Streamkeepers — a creek restoration group — captured some revealing video: an adult coho attempting to flip into the colossal culvert. Although the fish presumably gave up without spawning, the video was shared among fisheries folks associated with Streamkeepers and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). “That raised awareness,” says Robyn Worcester, biologist with Metro Vancouver. “Wild coho salmon were actually using the stream.”

After Kevin’s passing, Colin and Barbara Watson decide that “UBC needed some attention from us.” Passions of children can often be sourced back to their parents, and Colin Watson, too, loved the outdoors and had attended UBC. A former CEO of Rogers Cable Systems — and subsequently Spar Aerospace — Colin had grown up in Vancouver, a childhood spent many weekends at the gossamer end of a fishing reel, casting into Capilano River and the high-rising Lynn Canyon. To this day Colin flies to New Brunswick to catch-and-release Atlantic salmon on the renowned Restigouche River.

Although other options for their UBC donation emerged, it was Kevin’s connection to landscape that prompted his parents to fund the Salish Creek restoration. “If he were alive today,” Colin says, “Kevin would have thought it a dandy way to spend $250,000 of family money.”

The six-year project would involve so many partners and government jurisdictions that it almost emulated the layering and complexity of nature itself. How complex? The federal government oversees the tidal waters and creek itself, while the province protects the streambanks and land surrounding it. The drainage, meanwhile, winds through UBC Endowment Lands and Metro Vancouver manages Pacific Spirit Park, through which the lower creek becomes Burrard Inlet. And the Musqueam history runs under it all, having the longest stake in their unceded land. Just one century ago the peninsula was a diverse, thriving ecosystem.

“The reestablishing of this creek has not only significance to Musqueam people and for the long-term benefits to our wild salmon,” says Morgan Guerin, a Musqueam First Nation fisheries officer, “but also the identity of the area involved. With the cooperation of UBC and Metro Vancouver and the respect they have endeavoured to show Musqueam, this project is breathing life into this place that is well within our historical memory. Rather than ‘Here is something we used to own,’ we can say instead, ‘Here is something we belong to.’”

Yet the restoration would be slow. It would involve many government permits and stakeholder meetings, not to mention the cycles of provincial, federal and municipal sign-off. And as the project partners all understand, when humans attempt to revise nature, nature often resists, reconfiguring these efforts in unexpected ways.

After the Streamkeepers video was captured in 2011, engineers added baffles to the culvert: little ledges designed to interrupt and slow the current and allow spawning coho to amble and lever themselves upstream. But, in 2017 the project leaders discovered these weren’t enough to facilitate spawning.

“The fish couldn’t access the culvert,” says Barry Chilibeck, principal engineer at Northwest Hydraulic Consultants (NHC), the company contracted by UBC to carry out the engineering portion of the project in partnership with Ken Ashley, director of the Rivers Institute at BCIT. “The drop was too great, with the pool water too low.”

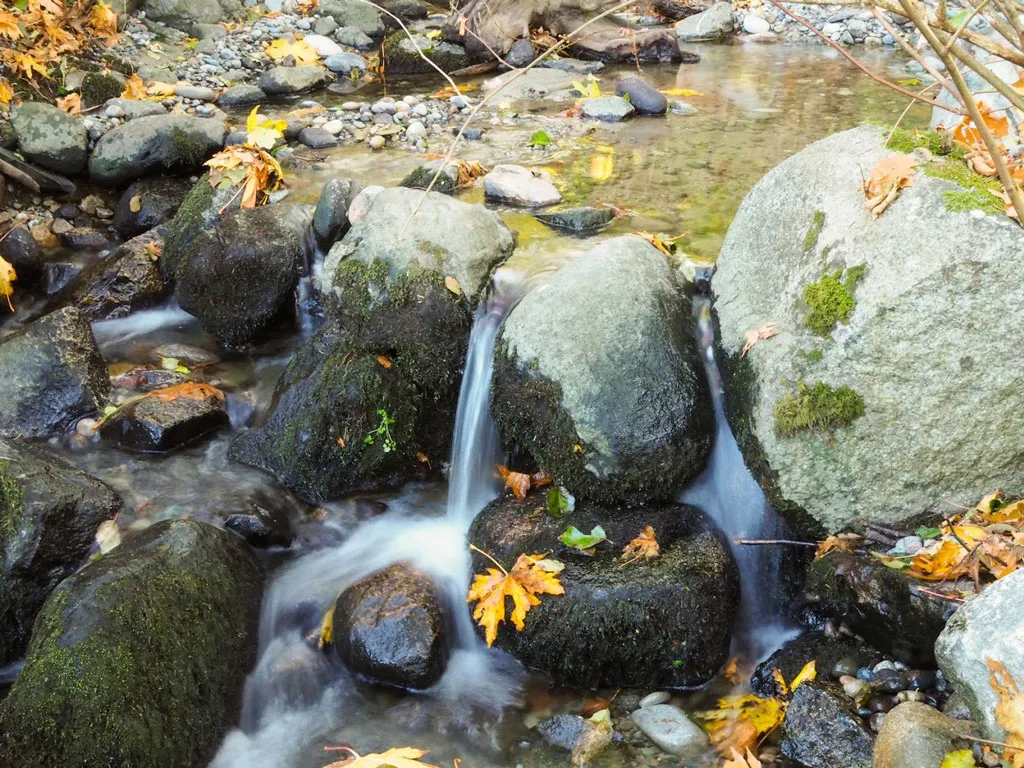

A healthy stream runs in a classic pool/riffle sequence, but Unnamed Creek had few riffles or pools. “This was impacted habitat,” Chilibeck says, “so we connected the creek to the ocean, restructuring the channel to make it more natural and complex.” NHC strategically arranged rocks to create riffles — adding oxygen as water bumbles over them — and log sills to fashion sandy pools in which salmon could spawn and hide from predators. Yet the area was still scribbled with English Ivy: an invasive species that shoulders out indigenous plants, many of which provide habitat for salmon and other animal and plant species.

Then, in September, 2017, the project leaders found something unexpected. As an archaeological impact assessment was being conducted to ensure that the reestablishment of Salish Creek wouldn’t disrupt the cultural heritage of the Musqueam, the digging unearthed what looked like human bones. The RCMP were immediately called.

“The bones were human and archaeological in origin,” as Greg Morrissey, the project manager of Kleanza Consulting, wrote in an email thread to other project members. “These remains will be handled, stored and reburied following protocols by the Musqueam.”

Another complication arose that spring, when a flood flashed the drainage; immediately the team grew concerned about displaced sills and rocks. The spring flood, DFO quickly ascertained, had fortunately spared their riffles and pools. Once again, the project was on, though it was four years along now, in part because the timing of this multi-partnered, collective effort had to follow the increasingly unexpected rhythms of the seasons.

“I admit I tried to talk Colin into moving to other projects,” says Don Mavinic, the UBC civil engineering professor who acted as principal investigator of the restoration. “But he had perseverance. He said, ‘I would rather have it happen here, because this is where my son went to school.’”

One summer day last year, Mavinic checked on the restoration site. As bulldozers groaned around the forest, replanting shrubs and trees, a Musqueam elder and Metro Vancouver employee chatted creekside. Not long after Mavinic introduced himself, a family of otters glided up the creek.

As Don recalls, “The elder said, ‘Our friends have come to welcome us.’ And I thought, ‘Wow, this is incredible. An out-of-body experience.’”

Since then, DFO has detected the occasional scurrying of salmon fry in the creek. While the fish, Robyn says, may not have originated from a “spawner,” it’s too early to determine whether salmon are actually returning to Salish; only time can reestablish the population. “Improvements to the creek,” Robyn adds, “have made it a more functional ecosystem. We are seeing contributions to other species as a result of the habitat restoration.”

On a recent visit to Salish Creek, Mavinic (now retired) noticed a school of cutthroat trout winnowing across the creek mouth. Unlike salmon, trout are plentiful here. “And I didn’t have my fly rod,” he joked.

Three small salmon also appeared, inscribed with the tell-tale markings of a coho. “I would recognize their spots anywhere,” he says. The fish were meandering upstream past boulders and logs and “to this day I don’t know if they spawned or not. I’ll never know because I had to return to class.”

View more photos from the Salish Creek Project recognition event.