Racism in Indigenous health: It still exists

Edited: July 5, 2022

Inequalities in healthcare

In 2020, the story of an Indigenous woman in medical distress made international headlines after a coroner's report found that racism played a part in her treatment and that her death could have been prevented. Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year old mother of seven, live-streamed the abuse by nurses at a hospital outside of Montreal before she died. It’s only by confronting stories like this that we can begin to understand the treatment of Indigenous Peoples—and their reluctance to seek treatment—in healthcare systems across Canada and the United States.

“They’re ignored, whispered about, the nurses assume you’re drunk or on drugs or that you’re drug-seeking,” says Dr. Margaret Moss, the interim Associate Vice President of Equity and Inclusion at UBC, as she starts listing the types of racism that Indigenous patients face. She has great insight into the issue being Indigenous and a nurse herself. “(The medical professionals) think you’re an incompetent parent, so parents worry about social workers taking their kids. They have to be hyper vigilant when seeking medical help because everything that happened to them out there—whether in school, in stores, on the bus—they come in and it’s the same thing.” It’s little wonder, then, that inequalities in health between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people exist in Canada.

“There is no safe harbour for an Indigenous person seeking healthcare,” reiterates Dr. Moss. “From the minute they call, they don’t know how they’re going to be treated, whether the intake people are going to roll their eyes or whatever, how they’re going to be treated by nurses. That causes a lot of stress.” Knowing this, Joyce Echaquan must have mustered up every ounce of energy to seek medical help. She probably knew she wasn’t going to be treated well, but surely she never imagined things would end up the way they did.

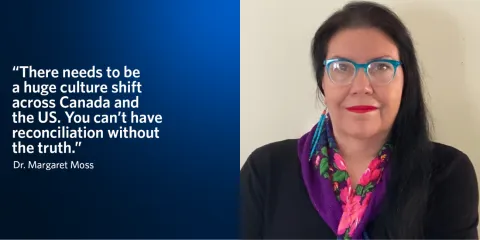

“There needs to be a huge culture shift across Canada and the US,” says Dr. Moss. “People have to know this happens.” She brings up the saying, “You can’t have reconciliation without the truth,” to illustrate her point, which is the need to actively confront the reality of what Indigenous Peoples face when they attempt to access healthcare. “But people don’t know the truth. You don’t learn it at school. You have to seek it out,” she says.

And seek she did. “Not one single resource,” emphasizes Dr. Moss. So she wrote one herself.

Published in 2015, American Indian Health and Nursing by Dr. Margaret Moss is the first textbook to examine the disparities in American Indian health and how they can be reduced.

Indigenous healthcare, as Dr. Moss explains, covers at least two major areas: the treatment of Indigenous Peoples in the healthcare system and the lack of respect for Traditional Indigenous Knowledge. “It’s just another knowledge system that’s been totally discounted,” she says, adding that Indigenous People in North America have had thousands of years to hone their healthcare systems. “They have a whole system of healthcare that is invisible to the West,” says Dr. Moss chuckling as she thinks about how some Indigenous groups approach the medical system we are most familiar with. “They find the West as ‘alternative medicine!’”

Indigenous Health in the News

Vancouver Coastal Health recently welcomed Elder Glida Morgan from Tla’amin Nation (north of Powell River) who moved to Vancouver to be a part of the maternal and family healthcare team.

But things are changing. Dr. Moss is heartened to see more education for healthcare professionals and involvement by Indigenous Peoples in the healthcare system. She co-taught Nursing 353: Promoting the Health of Indigenous People, a mandatory course for UBC nursing students. This past session they were able to hold their classes in the Longhouse, which Dr. Moss says was a great opportunity for the students to be in the space and learn from Elders who are revered for their knowledge and experiences in Indigenous cultures. It’s only by seeking the truth and taking action that racism in Indigenous health can finally end.

Learn More

Check out In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Health Care: full report or summary.