Indigenous scholarship recipient Larissa Tobacco bends design thinking to her pursuits in land stewardship.

Discovering “design” sounded straightforward enough. But as a first-year UBC Urban Forestry student, Larissa Tobacco didn’t immediately see what architecture had to do with her.

Larissa is clearly adventurous, though, and intellectually curious. When participants of the 2021 Design Discovery program in the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (SALA) were asked to dream up a city space where the private and public worlds intersect, she sketched out a series of “controllable screens” for a café that could turn, say, a public seating area into a private one (and vice versa).

And if that fascinating, digitally-inspired concept isn’t easy to visualize, the UBC student understands.

“I’m pretty abstract,” she says, laughing. A second-career professional, she already holds several postsecondary degrees, including a BA in Psychology. “I sometimes think I could be a career student, if I was blessed with the opportunity to be.”

Larissa is the first recipient of a new Indigenous scholarship to attend the Design Discovery program, a two-week intensive introduction to design for high-school and college students, graduates and second-career professionals. Interestingly, prior to this year’s workshop, two donors independently hit on the same idea: to help the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture build a base of diverse talent, specifically Indigenous talent. After all, design, like other professions aspiring to greater inclusivity, needs more diverse voices.

SALA, already committed to recruiting more Indigenous students and to decolonizing curricula, immediately welcomed these inspired donations. The Yosef Wosk Family Foundation generously contributed to the Design Discovery program, while the Architecture Foundation of British Columbia (AFBC) supported Larissa’s scholarship.

“We can only improve the current situation by improving access and diversifying opportunities,” says Karl Gustavson, the AFBC Board Chair. “Whether or not an award recipient continues on with architecture, I can’t say, but now the participant is aware of design and its potential.”

Larissa describes her own “design discovery” as an arc. If the concepts were somewhat fuzzy at the start, as they would be for most of us, “My eyes opened suddenly,” she says. “There was an arc from, ‘Where am I going?’ to ‘Oh, I understand this.’ I saw the world in a different manner.” In architectural design, she realized something simple and functional could also be aesthetically pleasing—and sustainable.

“It has to be sustainable,” Larissa says, who is pursuing a Bachelor of Indigenous Land Stewardship. “I’m all for, ‘Let’s keep the world going.’”

Design offers a flexible approach to the world, enabling students to shape their own experiences, according to SALA Director Ron Kellett. “Design is always reciprocal,” he says. Indigenous ways of knowing encourage reciprocal relationships between people and place, and “design schools have much more to learn about these ways.”

The Design Discovery Program Instructor, Architect and SALA Professor Bill Pechet, was enthusiastic for the experiences and ideas Larissa brought to the studio table. “Larissa was very clever at bringing in images and communicating her ideas,” he says. “She proved that a person can be resourceful and talk about a design idea, even if you don’t have all of the skills to design it yet.”

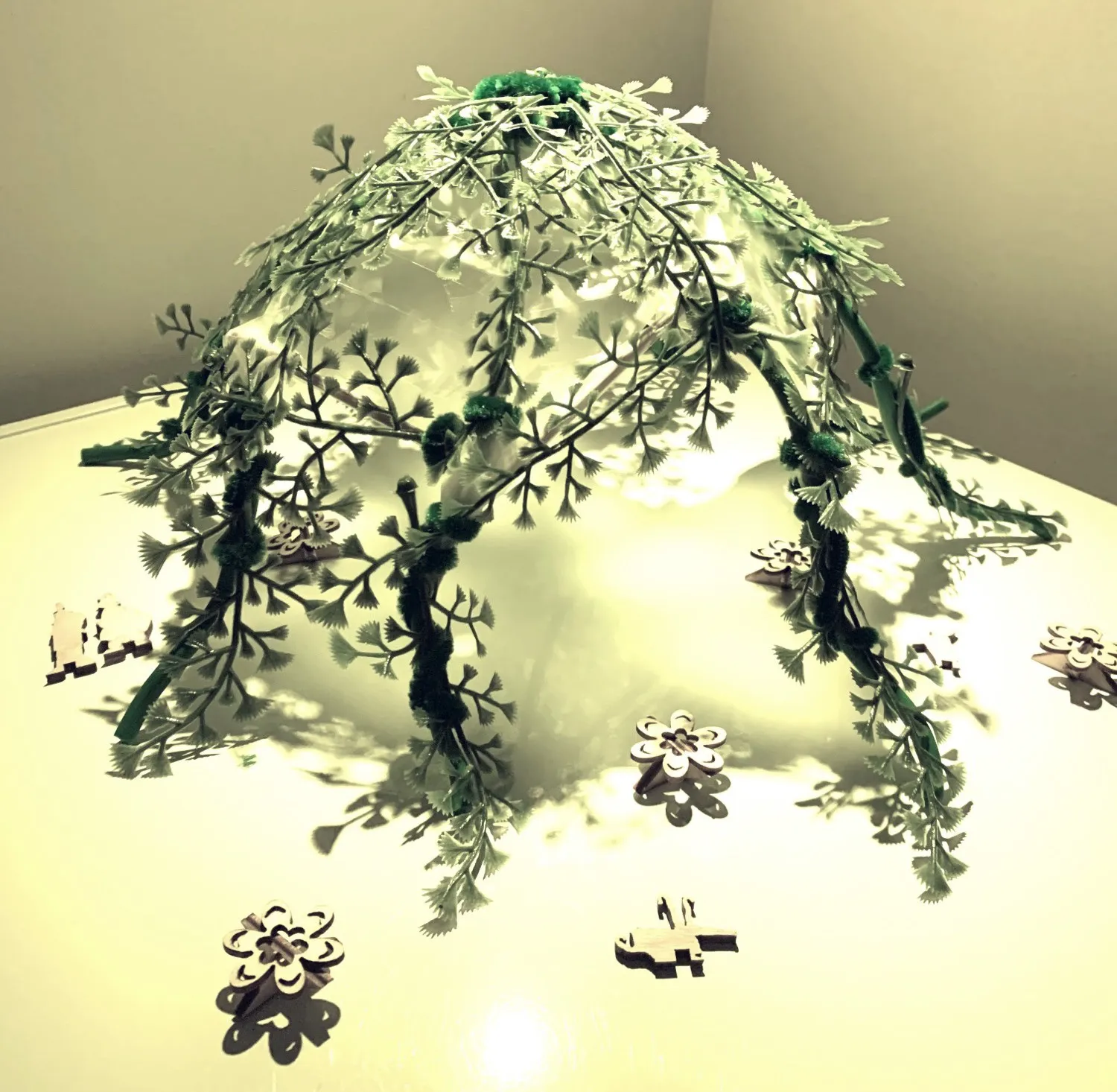

For her final workshop assignment, Larissa found a Pinterest image of an archway of climbing Evergreen Clematis. “I wanted to create a living gazebo,” she says, “and chose Clematis because it blooms all year long in Vancouver, which is a temperate rainforest.” Not only is the flowering aesthetically pleasing—it grows up, into and around the gazebo— giving her design a new functional turn that provides shading and cooling potential as well as UV-protection. “My living gazebo could be a setting for birthday parties, barbecues, weddings. Anything.”

Considering that the workshop took place in 2021—a summer squeezed between pandemic waves—the participation of Larissa and the other students was entirely online. Before the pandemic, Pechet would often take a “gaggle of students” downtown to study urban spaces in Vancouver, but COVID-19 forced him to devise a creative alternative: a virtual class that logs in around a simulacrum of a studio table. This move online, says Tara Deans, SALA’s Manager of Student Services and Recruitment, meant enrolment in the program leapt from around 20 to 60-plus participants, including students from South Africa, China, and South America.

Another way of expanding awareness of design education, says Deans, is to piggy-back on the efforts of Geering Up, a UBC not-for-profit program dedicated to STEM outreach in remote and Indigenous communities. Two “Making by Design” workshops are planned for communities next summer—a perfect opportunity for interested donors.

“If the donor wants to make a contribution, I think we could reach so many more people,” says Deans. “And that’s got me really excited.” With new programs and forms of engagement, SALA could attract and recruit diverse prospective students and be much more responsive to new voices, ambitions, experiences, and ideas brought to the design education table.

Excited at the prospect of possibly integrating design thinking with her Indigenous land stewardship education, Larissa points to her living gazebo as an example of how the fields of urban forestry and design could leverage one another.

“The living gazebo would have a basic wooden structure,” she says, “but evergreen clematis would merge with this structure to create a place that is also alive."