Black History Month Virtual Museum

UBC Applied Science

UBC Applied Science

Understanding Black history in British Columbia is crucial to understanding the modern Black experience in our province. This virtual museum was created by Bashir Mohamed, formerly the EDII Coordinator in Applied Science, and is intended to critically engage with our province's history, and to discuss the Black experience in British Columbia, UBC, and our Applied Science professions.

Visit our pop-up museum on Black history in the Fred Kaiser Building atrium.

Listen to the insights shared in our Black History Month Event

Listen to our panelists share their thoughts on the Black Experience in the Faculty of Applied Science.

The first Black settlers to British Columbia arrived in 1858. They came from California and arrived in the province just as the gold rush on the Fraser River was beginning. Some chased the gold rush while others settled in communities like Victoria and Salt Spring Island, where they worked as barbers, saloon keepers, and day labourers.

Early Black British Columbians sought to make an impact in the province but faced barriers, with segregation being common. This segregation led to Black people being barred from theatres, bars, and being barred from signing up as volunteer firefighters. Despite this segregation, 600 Black people immigrated to the province.

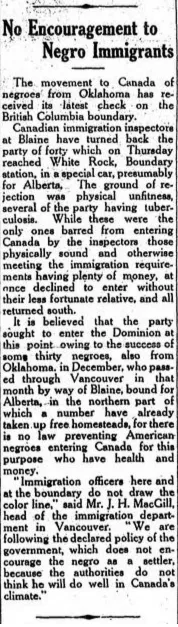

Soon after the American Civil War, many of the estimated 600 Black immigrants returned to the United States. The province never did receive another major wave of Black immigration. This was largely due to racist and unfriendly immigration policies that sought to limit Black immigration to the Canadian west. For instance, in the early 1900s, another large wave of Black American immigrants sought to enter Canada. However, they faced resistance and, as reported in the Orchard City Record (see side image), were refused entry into British Columbia.

“The movement to Canada of negroes from Oklahoma has received its latest check on the British Columbia boundary,” one immigration officer was quoted, saying, “we are following the declared policy of the government, which does not encourage the negro as a settler, because the authorities do not think he will do well in Canada’s climate.”

- Orchard City Record, April 20, 1911

Despite this resistance, Black people continued to exist in British Columbia with Vancouver’s Black community congregating in the East End between the 1920s and 1960s. The centre of their community was Hogan’s Alley, which became a “cultural hub.” Hogan’s Alley was later destroyed with no similar Black neighbourhood emerging to take its place.

Currently, Black British Columbians only make up 1% of the province's population.

Black History at UBC begins with the foundations of the university. The University of British Columbia was established with major assistance from McGill University and - before UBC's formal establishment - operated as the McGill University College of British Columbia. As past UBC President N.A.M. MacKenzie notes, "the work of McGill in British Columbia paced UBC to a flying start." In fact, half of the staff and more than half of the students during the first UBC session belonged to McGill. The first chancellor of UBC, F. Carter-Cotton, was chancellor of the McGill University College of British Columbia.

The founder of McGill University, James McGill, enslaved Black and Indigenous people. He also was a trader of enslaved Black and Indigenous people. This history is important to understand as the very foundation of our institution came from an individual who benefited from chattel slavery. The names of the enslaved people the McGill household "owned" are as follows:

This history provides the necessary context for the existence of our university and the underrepresentation of Black students, staff, and faculty. We must ask ourselves, if the very foundation of our university came from a slave owner, then what responsibilities do we have as members of this modern institution to create welcoming spaces for Black students?

Read more about Canada's 200 years of slavery.

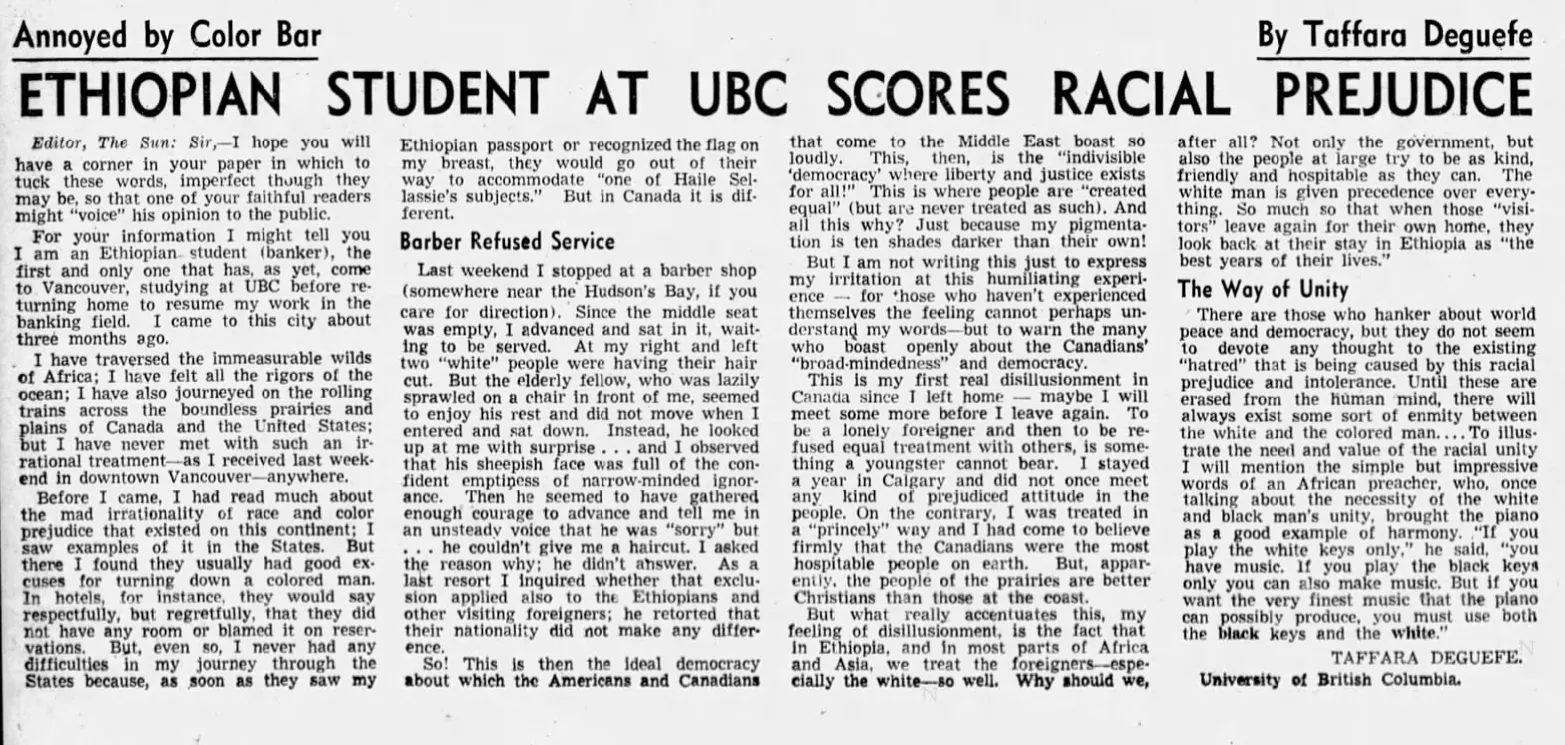

Black students at UBC faced segregation and barriers due to the colour of their skin. Taffara Deguefe, an international student from Ethiopia, was refused admission at a barbershop in 1947. In response, Taffara wrote an op-ed in the Vancouver Sun where he discussed his perspective on race relations in Canada. Taffara wrote:

“So! This is then the ideal democracy about which the Americans and Canadians that come to the Middle East boast so loudly. This, then, is the “indivisible democracy” where liberty and justice exists for all! This is where people are created equal – but are never treated as such – and all this why? Just because my pigmentation is ten shades darker than their own!

But I am not writing this to express my irritation at this humiliating experience – but for those who haven’t experienced themselves the feeling cannot perhaps understand my words – but to warn the many who boast openly about the Canadian’s “broad-mindedness” and democracy.”

Taffara would close his op-ed by quoting a preacher he met while traveling through Africa: “If you want the very finest music that the piano can possibly produce, you must use both the black keys and the white."

Tafarra would go on to become the Governor of the National Bank of Ethiopia. In his later life, Taffara served as an expert in international finance.

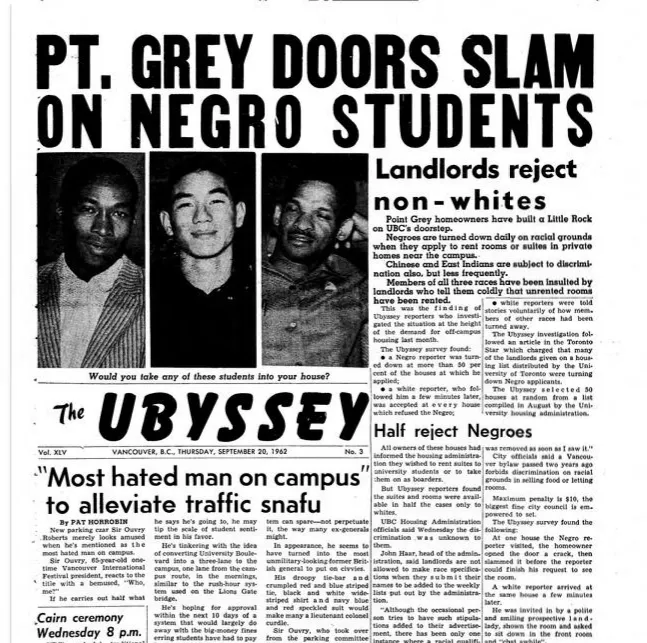

Anti-Black barriers continued and in 1962, "The Ubyssey" student paper did an extensive report on the struggles Black students faced in finding housing. The article declared that “Point Grey homeowners have built a Little Rock at UBC’s doorstep.”

The front-page story featured three students – two Black and one Asian – and asked the simple question, “would you take any of these students into your house?” Their reporting found that Black UBC students were turned down daily when they applied to rent rooms near campus. Chinese and South Asian students were also subject to discrimination, but “less frequently.”

The article directly quotes Point Grey landlords:

“I wouldn’t have a Negro in my house. They have a bad smell.”

“I don’t allow colored people in my house.”

“I’m not prejudiced but I know my neighbors are.”

These comments illustrate the historic barriers Black students faced in seeking to be part of our campus.

As members of the UBC community, we must interrogate the legacy of this segregation and explore how implicit and explicit racist attitudes continue to impact Black students on campus to this day.

Black people in Canada have a rich engineering history. The earliest examples include the Black soldiers of the No. 2 Construction Battalion – an all Black unit that previously served in World War One and worked on challenging construction projects.

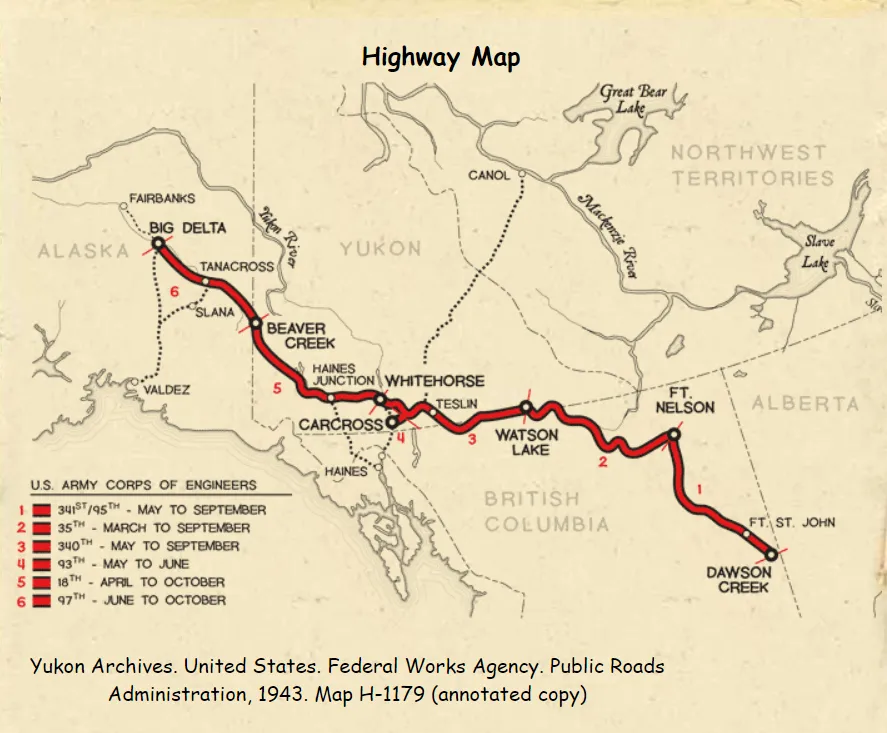

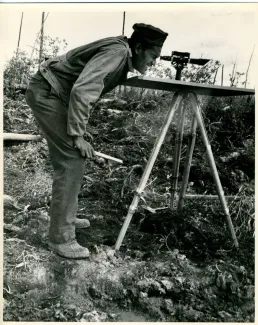

Black soldiers in British Columbia also have a rich engineering history due to their role in building the Alaska-Canada Highway. The 2,400 kilometer highway ran from Dawson Creek, BC to Delta Junction, Alaska. The 1942 construction of the highway was initiated due to the tactical necessity of building a supply route from the continental United States to Alaska, which was then under threat of attack by the Axis powers.

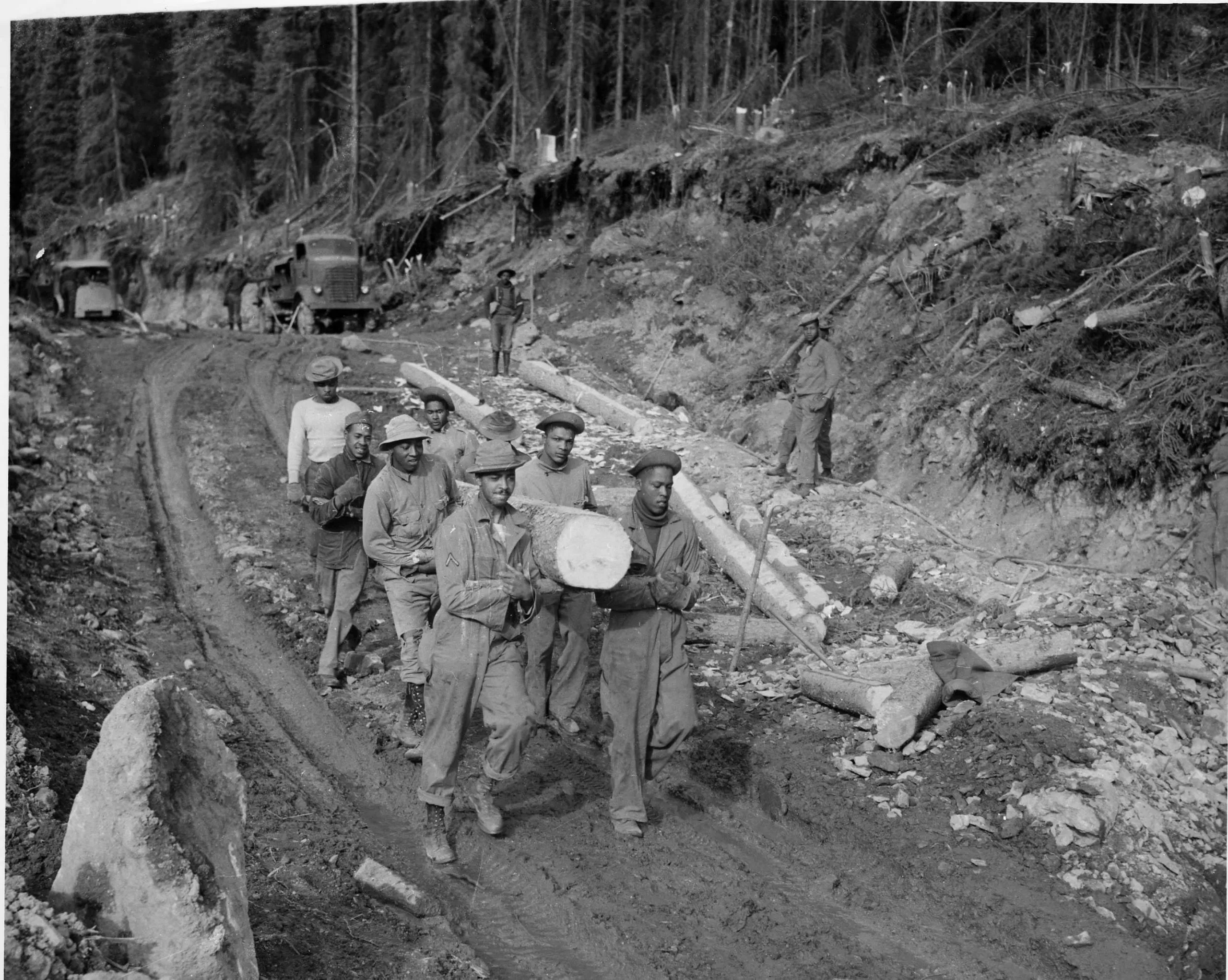

As a result, 11,000 soldiers were assigned the role of building this critical support hub. Four thousand of these soldiers were Black and belonged to segregated all-Black regiments. The Black soldiers faced discrimination with their commanding general – the son of a confederate general – forbidding the Black soldiers from gathering near Indigenous settlements due to fear that they would have children with Indigenous people.

The soldiers were also frequently “shortchanged” in their assignment of construction equipment. According to PBS, one such unit, the 95th Engineer Regiment, had their bulldozers given to the all-white 35th Regiment. As a result, the 95th was forced to work with mostly hand-tools.

The Black soldiers faced major challenges such as mosquitoes, permafrost, and extreme cold. Despite this, they persevered and rose to the challenge. In Sikanni Chief, BC, the all-Black 95th Regiment bet a month's pay that they could build a bridge across the river in four days. They completed this task in three days.

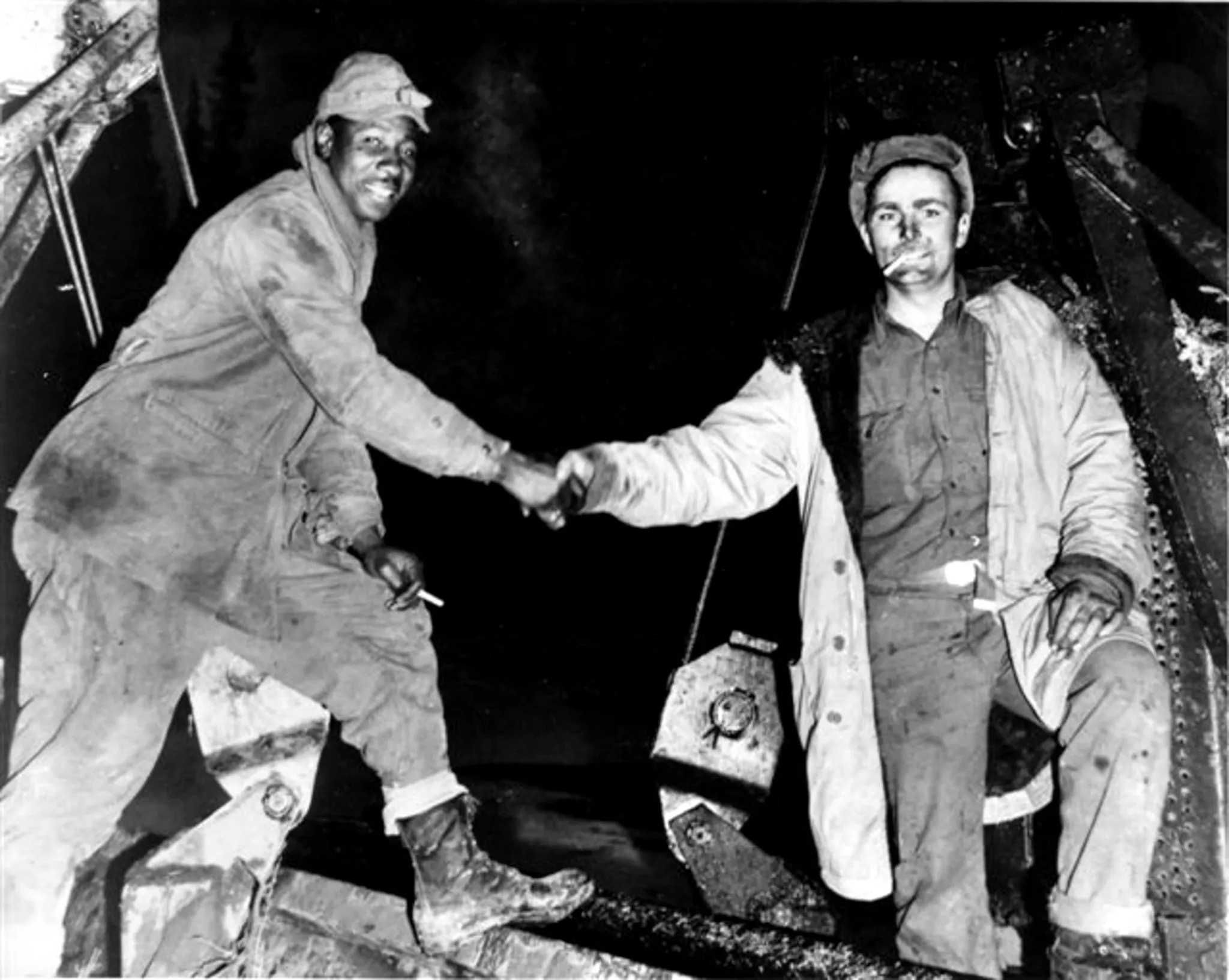

On October 25th, 1942, Corporal Sims Jr. and Private Jalufka stood on a bulldozer and shook hands, symbolizing completion of the Alaska-Canada Highway. The highway still exists and connects British Columbia with the Yukon and Alaska. If you ever drive this highway, think about the Black soldiers who built the highway through the cold weather and even colder segregation.

Eldson Gladwin, the first Canadian Army Officer to drive the pioneer road, described his experience witnessing the construction of the highway:

"Those U.S. troops - I felt sorry for them to begin with - then was amazed at what they did. If you weren't there, you just couldn't understand it. I saw fellows so tired, they were ready to drop in their tracks. It was rush-rush-rush! Fellows were doing 18 to 20 hours a day on bulldozers. One was up to his neck in ice water repairing timbers in subzero weather. God, I admired them! Most were southerners - they'd never experienced cold like that. And in the summer, it was mosquitoes - like they'd eat you right there, or pack you away to eat at home."

In 2017, the soldiers were honoured by the State of Alaska for their contributions to the construction of the highway.

The Black women that fought segregation in the nursing profession

Sylvia Stark was among the 600 Black pioneers that immigrated to British Columbia in 1858. Born into slavery, Sylvia immigrated in 1858 and settled on Salt Spring Island because she felt that the land prices on Vancouver Island were too expensive. Sylvia and her family farmed the land and she also practiced community care as a midwife.

According to UBC PhD student, Ismália De Sousa, Sylvia’s role in community care and public healthcare is an early example of Black nursing in Canada. As De Sousa notes, “while we don’t know to what extent she was pressed into service to help others, her description of herself as a nurse suggests that in some ways, she was a keeper of community health.”

Sylvia was not the only Black practitioner of community health. Adelina Phelps and Nancy Alexander also worked as midwives within the Black pioneer community. You can learn more about these early nurses by listening to the panel talk, “Black (in)Visibility: Black Nurses in Canada who paved the way.”

Archival records across Canada reveal a long and systemic legacy of segregation within nursing schools in Canada. The first nursing school in Canada opened in 1874 but Black women were not permitted to train in these schools until the 1940s. Instead, Black women were often told to enter the United States to work in their dedicated “Negro Hospitals”

This segregation was centered on racial prejudice and was centered on the idea that Black women were somehow inferior and that white patients would not want to be treated by a Black nurse. Most examples of this segregation are centered on Eastern Canada but there are Western Canadian examples of segregation too. One such woman who was denied entry into the profession was Rhumah Utendale in Edmonton, Alberta.

Rhumah was a star high school student and had the grades necessary to enter the Royal Alexandra Hospital Nurses Training program. However, she was refused admission due to her race and a feeling that white patients would not want her care. Due to this systemic racism, Rhumah was denied the career she longed to enter. Years later, an opinion piece was published in local newspapers expressing outrage at her refusal:

“I have been in another country for the past two weeks. They have a racial problem about the handling of which Canadians can wax righteously indignant. Sheer hypocrisy, most of it. We talk about racial equality and when it gets down to cases we react just the same as the people we condemn. A very fine negro girl made application to train as a nurse in our publicly-owned hospital in Edmonton a few years ago.

She was at first accepted because there was no excuse not to accept her. She had every qualification – and she greatly wanted to be a nurse. And then our boasted Canadian racial tolerance came to trial – and failed miserably. Because she was colored, the girl was denied the right to the career she longed to enter.

Question: Might she have been better off under the segregation employed in the southern states? At least there she could have become a nurse, trained in a negro hospital. We denied her that chance.”

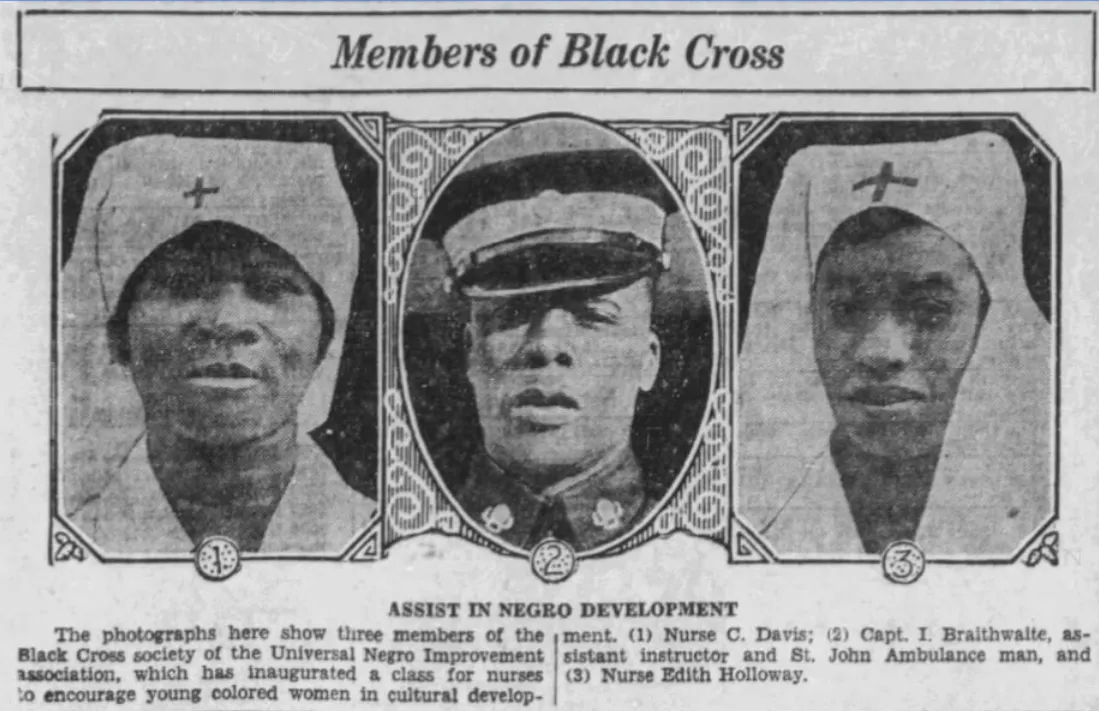

Despite these barriers, Black women organized and created the Black Cross Nurses (BCN) in the 1920s. The BCN was an institution focused on promoting community health and was a place of “unity and friendship” for Black women. The BCN had chapters across Canada in cities like Vancouver, Edmonton, and Toronto.

Despite not being formally trained as nurses, the BCN worked as community health care providers and took ambulance courses. In 1921, the BCN in Edmonton was reported to have answered “250 calls to sick community members.” This work was crucial as Black patients were often barred entry into Edmonton hospitals in the 1920s and 1930s.

Beside their healthcare function, the BCN also did cultural programming as a way to celebrate the Black community. This took the form of organizing garden parties, bake sales, and dinners. The work of the BCN is important in understanding that despite being barred from formal nursing training these Black nurses took it upon themselves to provide critical healthcare for their communities.

Desegregation in Canadian nursing schools largely happened due to the activism of Black women across Canada. Pearleen Oliver, the founder of the Nova Scotia Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, challenged the exclusion of Black women in nursing schools and was successful in allowing the admittance of Black women into some nurses training schools.

Desegregation occurred slowly and took effect in the 1940s and 1950s. While the barrier of segregation was removed, Black women continued to face barriers in their training due to explicit and implicit racism. These barriers and racist attitudes can be seen beyond nursing and within the medical field at large. One such example is found in Saskatchewan. In 1928 the Ku Klux Klan donated a medical ward to the Moose Jaw Hospital. Affixed to the ward was a plaque dedicated to “Public Schools, Law and Order, Separation of Church and State, Freedom of the Press, White Supremacy.”

In 2022, a systematic review was conducted of Black nurses in the nursing profession in Canada. The review found that modern racism and discrimination within the profession can be traced to the “historical situatedness of Black nurses in Canada.” Modern data on the number of Black women in the nursing profession is hard to find. What we do know is that Black women are largely absent from leadership positions within the profession and are often placed in entry-level, non-specialty positions. Data also shows that Black women continue to face barriers due to explicit and implicit racism within the nursing profession.

The destruction of Hogan's Alley: a story of displacement via urban planning and architecture

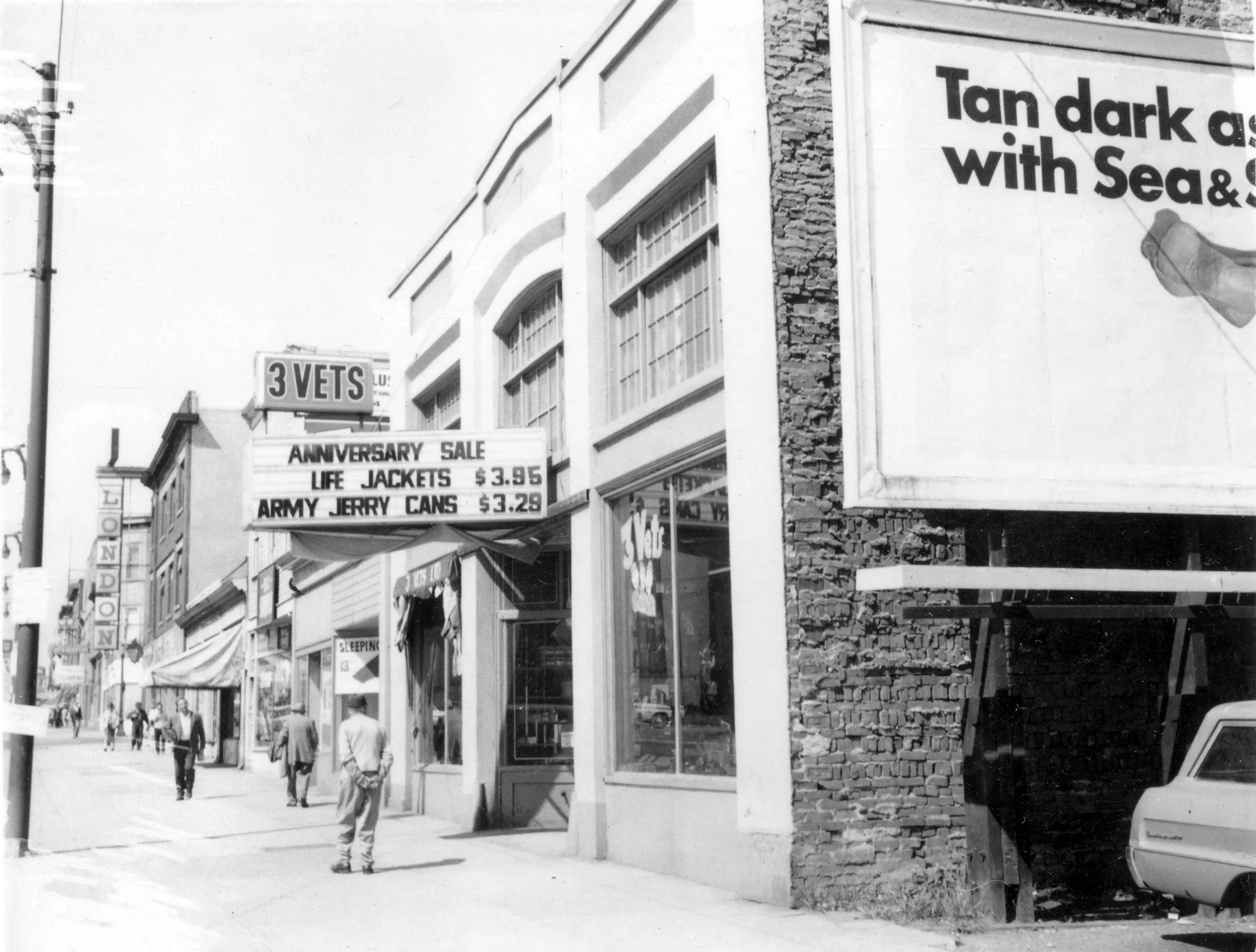

Hogan's Alley, the unofficial name for Park Lane in Vancouver's Strathcona neighbourhood, was home to Vancouver’s Black community. The alley was located between Union and Prior Streets from Main Street to Jackson Avenue. The neighbourhood was established in the late 1800s and early 1900s following the initial arrival of Black pioneer settlers from San Francisco in 1858.

The community was centered on the east side neighborhood of Strathcona. As the neighbourhood grew, it drew in “Black homesteaders, emancipated slaves, railway porters, and traveling entertainers.” The neighbourhood remained a central community hub until its eventual destruction in the 1960s and 70s.

Hogan’s Alley was home to cultural and entertainment hubs but it also served as a base for the Vancouver Black civil rights movement. Nora Hendrix (Grandmother of Musician Jimi Hendrix) moved to Vancouver in 1911 and helped establish the African Episcopal Church congregation in Vancouver. The congregation was located in Foundation Chapel on 827 East Georgia Street.

In 1952, 52-year-old longshoreman Clarence Clemons, was violently beat by Vancouver Police Officers and eventually died of his injuries. The community was outraged and used the Foundation Chapel as a central organizing point. The Pacific Tribune quoted Clarence’s friends who said, “talk to his friends, negro and white, and they will tell you the man responsible for his condition in General Hospital is a “Negro-Hating cop.”

The officer, Constable Dan Brown, was reported as the one who “punched, pummeled, and kicked Clemons into the ground.” An investigation into the beating, decided by a jury consisting entirely of white middle-class residents, ruled the death an accident, declaring that Clemons died due to a “pre-existing” condition.

Immediately after the verdict was read, an unidentified Black man stood up in the courtroom and asked if he could ask a question. The police immediately shouted at him to be quiet but the man continued and said, “I’m not satisfied with this verdict, I want to ask a question.”

The coroner threatened the man and said, “sit down, or we’ll take you upstairs and let you ask your questions up there.” The man sat down as officers moved in on his position.

The outrage from the Clemons' verdict led to the establishment of the Negro Citizen’s League in 1953. The Clemons story illustrates the systemic barriers Black Vancouverites faced in the justice system. Many of these barriers still exist, as Black Canadians continue to be disproportionately represented within the criminal justice system. Additionally, Black Vancouverites are also disproportionately "carded" at higher rates.

At its peak, the Black population in Strathcona numbered approximately 800. Despite its critical importance to the community, Hogan's Alley faced opposition and barriers from the city of Vancouver. In the 1930s, the City of Vancouver changed the neighbourhood's zoning regulations, making it harder for people to secure mortgages. The city eventually labeled the area a “slum” in order to prevent residential development.

According to the BCBlackHistory.ca, in the 1950 and 60s the city stopped maintaining the roads and sidewalks, causing the community to disperse. In 1958, Vancouver City Council launched a “redevelopment plan” that demolished the neighborhood. New construction was prohibited and property values crashed.

Finally, in 1967, the entire area was leveled for the construction of a new viaduct, effectively destroying the neighbourhood along with portions of nearby Chinatown.

Compton explains that putting the highway, “right on top of this small Black community” was an “example of institutional racism, targeting the community they thought could least oppose them."

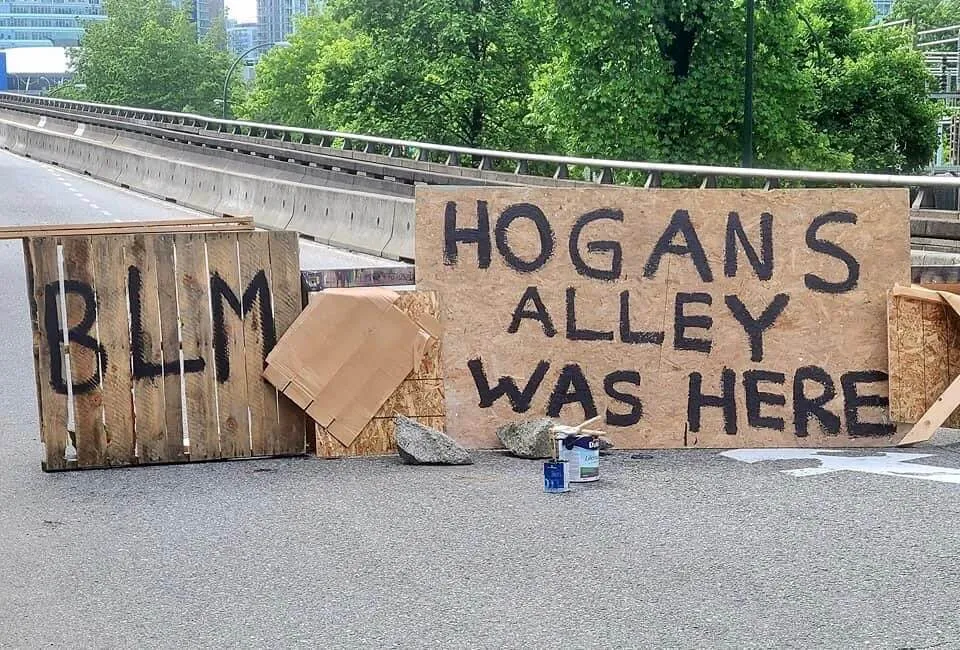

In 2020, Black Lives Matter protests spotlighted the destruction of Hogan's Alley with the community demanding that the neighbourhood be remembered and that the harm of the destruction be repaired.

Currently, the Hogan’s Alley Society exists as a non-profit organization to highlight Black history in Vancouver and to ensure the legacy of Hogan’s Alley is not forgotten. The organization is also currently negotiating with the City of Vancouver over the future of the site where Hogan’s Alley once existed.

“Unlike elsewhere in Canada, BC has no Black “ethnoburbs”, a geographer’s term for suburban neighbourhoods in which a particular ethno-racial minority group makes up the majority of the population. In Halifax, there’s Mulgrave Park; in Toronto there’s Rexdale and Jane and Finch; in Montreal there’s Little Burgundy,” he explains. “These are known, named places with concentrations of Blacks. Strangely, in Vancouver, a major Canadian city, there are no Black neighbourhoods. So there’s nowhere to go where you’ll see a high concentration of Black people or where you can be among Black people. We’re so dispersed that we are negligible."

While the harm caused by the destruction is being repaired, we must again consider how the destruction of Hogan's Alley impacts Black Vancouverites to this day. We must also consider the role our disciplines had to play in the destruction of Hogan's Alley. The multi-decade effort to destroy Hogan's Alley - such as the zoning changes, removal of civic services, and the design of buildings that "replaced" Hogan's Alley - directly connect to the disciplines of community planning and architecture. In addition, the actual construction of the Georgia Viaduct also connects to the Engineering discipline. This highlights the importance of understanding the impact all of our work in the Applied Science can have on the communities we live and work in.

Learn about John Sullivan Deas, the Black settler who spent 15 years in Delta, who was described as "a man before his time". Deas Island is named for John Sullivan Deas, and prior to being renamed as the George Massey Tunnel, the tunnel linking Richmond to Delta was called the Deas Island Tunnel.

The Faculty of Applied Science – in conjunction with the Faculty of Science – is proud to be a platinum sponsor for the BE-STEMM 2023 Conference.

The conference promotes Black excellence in STEMM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics, Medicine & Health) and will feature talks, panel discussions, and a virtual career fair.

UBC is located on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm people (Musqueam; which means 'People of the River Grass') and Syilx Okanagan Nation. The land has always been a place of learning for the Musqueam and Syilx peoples, who for millennia have passed on their culture, history and traditions from one generation to the next.